Will the World Humanitarian Summit pass the accountability test?

As the long run-up to next year’s World Humanitarian Summit gathers pace, a legitimate question is whether it will ratchet up pressure on the humanitarian system to do a better job. Bringing global leaders together to focus on a single topic can fast-forward change. Think Rio 1992 and the global environment. But will that same wind of change be blowing through the Istanbul summit in March 2016.

The big-ticket item on the agenda is making humanitarian action more effective. That is something devoutly to be wished for but it’s hard to negotiate in a UN setting with scores of government representatives surrounded by the serried ranks of the UN, the Red Cross and non-governmental agencies. In truth, we don’t need a blueprint for effectiveness. Better by far would be for the Istanbul summit to administer a dose of transparency to the humanitarian system.

Etymologically, transparency is a neutral term; something you can see through. But in the real world, it’s a yardstick of probity and accountability. In Europe and North America, the historical narrative runs from the obscurantism of the Dark Ages to the Enlightenment and on to the transparencies that underpin many of our institutions and behaviors today.

While we celebrate this linear progression we are vigilant in protecting and nurturing transparency’s purifying magic because it’s not an easy option. It is all too human to hold the cards close to your chest – to be “economical with the truth.”

Most of the progressive systems we know today were pulled kicking and screaming from behind the curtain of self-legitimacy and exclusion. While there is progress towards greater transparency and accountability, the humanitarian system has yet to renounce fully the comforts afforded by that curtain.

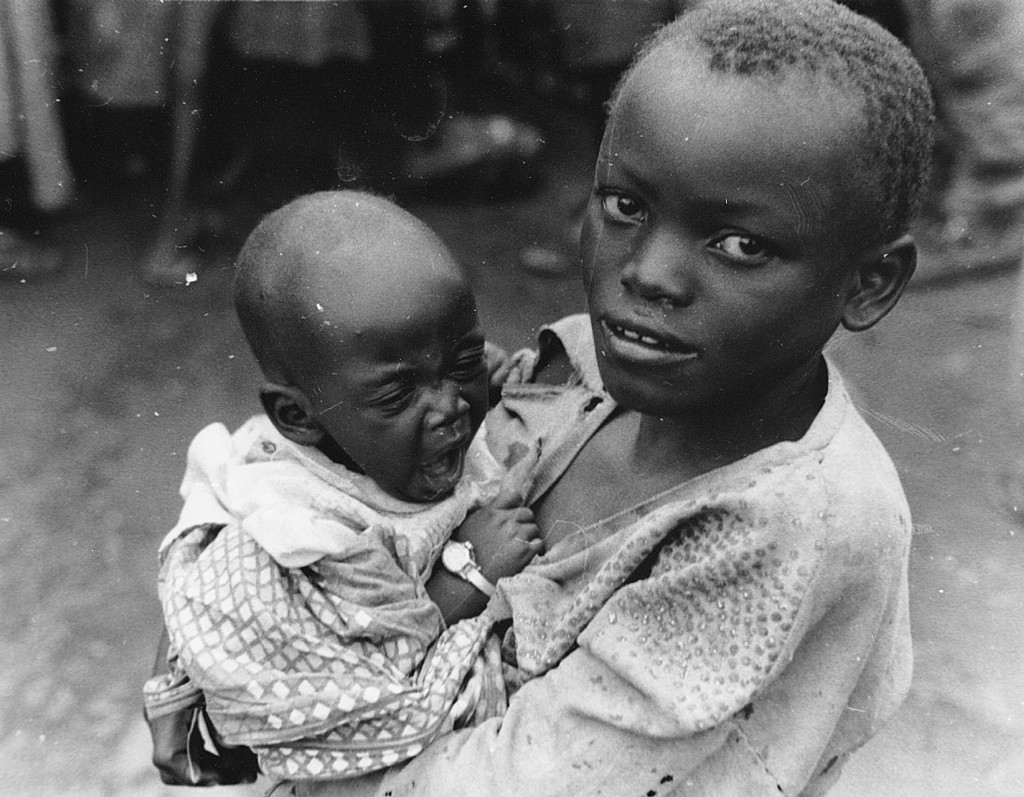

It may feel like an indignity to be held to account by people who you’ve traditionally seen yourself as representing. Putting people in the driver’s seat, however, is not only the right thing to do but the single best way to promote greater effectiveness in what, according to the 2014 report from Global Humanitarian Assistance, is a Euro 22 billion a year industry.

With so much money on the table, the UN, the Red Cross and the big NGOs compete strenuously but their competition does not necessarily translate into the kind of efficiency that delivers timely, relevant aid. This is because it is less about being the most effective agency and more about portraying yourself as aligned with the angels or, if that’s not credible, asserting the perquisites of your mandate. Too few humanitarian agencies strive to build a value proposition based on giving voice to the people on the receiving end of aid.

History suggests that if affected people are given voice, the humanitarian players will sit up, listen and act on what they hear. There are encouraging developments as donors like the SDC and DFID, the US Congress and an advance guard of operational agencies push ahead with practical approaches that put beneficiaries to the fore. But there are also plenty of leaden excuses about ‘complex operational contexts’ and the ‘risks associated with our work’ that slow the introduction of these tools.

If accountability is to have its transformative way in the humanitarian space, it will owe a lot to the framework of standards and codes of humanitarian conduct established over the last 15 years. The Core Humanitarian Standard, which brings together SPHERE, HAP International and People in Aid, is a great leap forward in terms of clarifying the pieces of the accountability puzzle and creating an actionable system.

The test for Istanbul is whether it is able to agree on a robust system to ensure that agencies take ownership of these supply-side initiatives. The cut-through way is to oblige organizations to collect feedback systematically from people affected by humanitarian disasters and to demonstrate how it is used to improve the response. By oblige, I mean make it obligatory.

There’s a chance that by the time UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon gavels the World Humanitarian Summit to a close, there will be consensus around this kind of system upgrade. Leonard Cohen describes well my hesitant optimism: “There’s a mighty judgment coming, but I may be wrong”.